The Temple's last mission

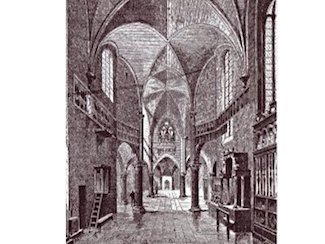

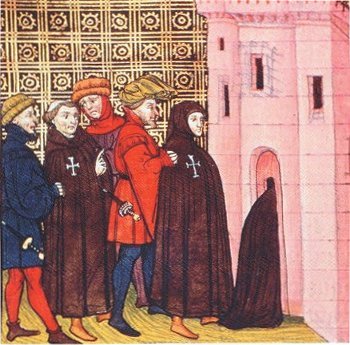

At the crack of dawn on Friday October 13, 1307, the king's troops, led by Guillaume de Nogaret, invest the Temple of Paris. All Templars present are put under arrest. The same day, in all the Temple'scommanderies of the kingdom of France, the same scene is repeated.

In Paris, 138 Templar knights are arrested. Amongst them, the Grand Master, Jacques de Molay (1292-1314) and a few dignitaries of the order attending him. The Templars don't offer any resistance to the King's men but Guillaume de Nogaret is disappointed: the Temple's enclosure is empty, the treasure is gone, and most of the Templars present are only sergeants or tradespeople. Only a handful of dignitaries are present during the arrest, standing for their order.

Obviously the knights have been warned about the upcoming raid against them. For Nogaret, the person responsible for the leak can only be his predecessor, the Archbishop of Narbonne, Gilles Aycelin. Indeed, Gilles Aycelin had strongly objected when Philippe The Fair (king of France from 1285 to 1314) had informed him on September 22, 1307, in the abbey of Maubuisson, of his intention of arresting all the Templars. Gilles, in his official capacity as Chancellor and Keeper of the Seal, had argued that the judicial proceedings were unlawful. Facing the king's unyielding determination, Gilles Aycelin had resigned his office.

The Grand Master of the Templars probably knew about the king's plans very quickly, maybe as early as September 22 and so made the necessary arrangements. Crates containing the Templars' treasure were loaded onto a dozen horses and taken away to a safe place by Gerard de Villiers, the new Visitor of the Order, escorted by forty knights in arms.

As the news broke, there was a commotion within the Temple's enclosure: the knights knew about the king of France's intention to arrest them but they didn't know when they would be taken into custody, and everybody tried to put their belongings under cover before the arrest which could occur at any time.

Hugues de Pairaud, Master of the Province of France, chose to entrust his treasure to Pierre Gaudès, Commander of the houses of Dormelles and Biauvoir, near Morêt en Gâtinois. Pierre Gaudès fled form the Temple with the safe, then handed it over to a fisherman in Moret-sur-Loing. The fisherman hid the safe under his bed. When the Templars were arrested, he brought the chest to the king's bailiff and the 1189 gold coins and 5010 silver coins in the chest were nimbly forwarded to the king's treasury.

Preferring to distance themselves from the king of France, the dignitaries of the Temple and the Grand Master Jacques de Molay had settled in Poitiers, close to the papal court. In early October, Jacques de Molay went back to Paris for the funeral of Catherine de Courtenay who was the wife of Charles de Valois, the king of France's brother. Riding back to the Temple's enclosure, the Grand Master and the few dignitaries coming with him could legitimately worry about the fate awaiting them: as they attended Catherine de Courtenay's funeral on the 12th October, they had the irrepressible feeling it was their own burial they were going to. Jacques de Molay, aware that once the Holy Land had been lost the times had become unfavorable to the Templars mission, wanted to face his destiny and stay faithful to his commitment. He was burned alive at the stake in Paris on March 18, 1314, his eyes turned towards Notre-Dame.

When made prisoner, Jacques de Molay didn't deny or contradict the charges leveled against him by the Inquisition serving the royal justice. It is possible that Pope Clement V (1305-1314) had convinced him to waive the defense of his order for the sake of the Church. The pope, seeing how aggressive the king of France had already been towards the Holy See, must have believed this strategy was the best way toprotect what was most important to him.

What was most important to Clement V, was the independence of the Roman church, gained at great cost during the last centuries from the feudal law. It was also important for him to preserve the interests of the Papal States established in the kingdom of France; namely the Venaissin County where the pope would find refuge when, after residing in Poitiers, he would settle the papacy durably in Avignon.

But by letting the king of France discredit an institution such as the order of the Templars, Clement V sullied the Benedictine tradition, and in particular the Strict Observance from which the Templars order came. Indeed it was Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, cistercian abbot of the Claire Vallée, emblematic figure of Christianity and of monasticism of the Strict Observance, who had been chosen by the Troyes council in 1129 to be the spiritual father of the Templars and to supervise the writing of their Rule.

Without even being aware of the consequences of his acts, Clement V was causing Christianity to regress , back to the limits of the barbaric times when the pope Etienne II (752-757) had knelt down before Pepin the Short (715-768), granting the imperial title and papal support to the frank dynasty in exchange of a few Papal States in Italy.

When in 1304, at a time when the King of France was still full of praise for the Templars, they rejected his request to join in the order, and when, in 1306 Jacques de Molay refused the pope's suggestion to merge with the Hospitallers, the Templar knights acted as they did because they believed they were the guardians of a world, the world of the Benedictine Strict Observance which had inspired the institutions of the first Latin States of Jerusalem. As the Grand Master wrote in his dissertation for Clement V on the merger of the orders, the Templars considered themselves the “vanguard of Christianity”.

When the Templar knights understood that everything was over and that they would witness the end of their religion, their first concern was to preserve the future. They had first of all to protect their treasure, which resulted from their undertaking in the Holy Land. This act of preservation was not meant to shield their wealth from the greed of powerful people who were always in need of funds, but rather to reserve a legacy for future generations. Through their treasure, the Templars set a date for us with our history.

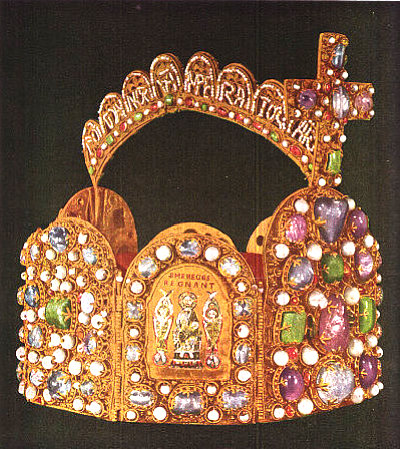

The Crown of the Three Magi

In 1372, a time when Pope Gregory XI (1370-1378) was seeking to revive the project of a crusade, a Carmelite friar, John of Hildesheim, prior of the convent Marienau, revealed some information about the treasure of the Templars and particularly about a key piece of this treasure. It was a crown of gold adorned with gems of inestimable value. The crown was surmounted by Chaldean letters and a cross. According to the description given by the prior of Marienau, it was very similar to the Ottonian crowns of the Holy Roman Empire.

John of Hildesheim also said that this gem was brought to Saint-Jean d'Acre in 1200 by the noble princes of 'Vaux'. Behaving like the Magi Kings, the nobles of Vaux deposited the crown with the Templar knights in the Holy Land. The Carmelite prior added that the nobles of Vaux also brought books on the Magi Kings and that they bore on their banner the Cross of the Temple and the Star of the Magi.

Marianne Elissagaray, who published in 1965 the Historia Trium Regum of John of Hildesheim, easily identified these magi kings with the House of Baux de Provence. The lords of Baux claimed they were descended from the Magus Balthazar. Their coat of arms has a star of 16 silver rays in honor of the Three Magi. Their motto was “Al'azardBeautezar.”

Coat of arms of the House of Baux

As for the books the Baux are said to have brought with them, they lead us directly to a literary tradition: the vaticinations, the writing of prophecies. The best known of these literary traditions in the Benedictine world of the Middle Ages was the millenarian tradition relating the end of times which was to happen in the Valley of Jehoshaphat in Jerusalem - place where they located the tomb of the Virgin Mary. The millenarian theories directly influenced the spirit of the knights of the First Crusade. When Godfrey de Bouillon (1099-1100) was appointed at the head of the new states of the Holy Land, he founded a monastery in the honor of the Virgin Mary in the Valley of Jehoshaphat and entrusted it to Benedictine monks. When the order of the Poor Knights of Christ Temple of Solomon was created in Jerusalem in 1119, the Templars became the protectors of the Valley of Jehoshaphat.

The Latin stories about the end of times are based primarily on a text of Syrian origin dating from the late seventh century and attributed to the Bishop Method. This story inspired a large body of prophetic literature, the most famous in the Middle Ages being Nativitate and obitu Antichrist written around 954 by a Benedictine monk named Adso of Moutier-en-Der. There was also The oracle of the Sibyl Tiburtina, composed in southern Italy in the mid-eleventh century. All these writings tell pretty much the same story: the coming of the King of the Last Days who will unify the Western world and will go to Jerusalem. There on the Mount of Olives, he will resign his crown and scepter. Bear in mind that Godfrey of Bouillon refused to wear the crown of Jerusalem where Christ had suffered a martyr, wearing a crown of thorns. The abolition of monarchy was to precede the coming of the Antichrist and his defeat by the Archangel Michael and his celestial legions, announcing Judgment Day.

According to the Benedictine tradition, it is in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, at the foot of Our Lady's tomb, that the Virgin Mary will intercede for her sons on Doomsday and that the proud will be condemned and the humbles consoled. Several monks of the Benedictine Strict Observance took an active interest on these revelations, namely the cistercian monk Otto of Freising (1112-1158), abbot of Morimond and uncle of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Otto's main concern was to demonstrate the Germanic character of the King of the Last Days. There was also Joachim of Fiore (1130-1202), abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Corazzo, daughter-abbey of the Claire Vallée. In his Expositio in Apocalipsim Joachim placed the end of time in 1200. But for the Cistercian abbot the end of time was just the beginning of a new era, the era of the Holy Spirit, which for him was the full realization of the Strict Observance Benedictine on a universal scale.

Undoubtedly the prophecies made by the Calabrian abbot were taken very seriously by the mysterious King Magi fraternity Jean of Hildeshem wrote about. The crown brought to the Holy Land was intended for the new Germanic Emperor elected in 1198, Otto IV of Brunswick (1176-1218), who on the day of epiphany 1200 had given three crowns to the cathedral of Cologne where the relics of the King Magi lie. Otto IV appears on the gold reliquary containing the relics of the Magi. He is portrayed behind the three kings, smaller than they are, and without a crown, as a sign of humility. He is also shown hands veiled, carrying offerings, because he is the donor of the gold and the precious stones decorating the reliquary. Otto IV was thus putting his coronation under the protection of the Virgin Mary and under the figure of the Christ on Doomsday, set above, on the upper part of the reliquary.

Otto IV of Brunswick-Poitou, grand-son of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry Plantagenet II, nephew of the king of England Richard the Lionheart, is also the famous hero celebrated in Parzival written by the German knight Wolfram von Eschenbach . But the requirements of the Benedictine Strict Observance world are demanding, and it is not uncommon in politics that the elected ones end up taking for their own good what they had only been entrusted with. Otto of Brunswick will soon disappoint his protectors, the Templars, and the Magi fraternity will have to find another representative.

In Provence, near the city of Arles, the Magi tradition is still very lively and is as ancient as the one in Cologne or Milan, and older than the one in Florence, where the Magi fraternity met in the private chapel of the Medici during the fifteenth century. The Magi fraternity still scanned the heavens long after the end of the Templars order and the vaticinations never stopped.

The most famous magus in Provence was Michel of Nostredame (1503-1566), author of the Centuries, whose name is made with the names of the two last protagonists on Doomsday in the Valley of Jehoshaphat. Michel of Nostredame was born in Saint-Rémy of Provence at the foot of the fortress of the Lords of Baux of Provence, in the Alpilles. This may just be a coincidence, but if you consider that the Templars hid their treasure in the expectation that the King of The Last Days would come and establish the state of the Strict Observance in Jerusalem, the indications given by Nostradamus in his Centuries concerning the location of the treasure have good reasons to draw our attention:

Beneath the oak tree of Gienne, struck by lightning,

the treasure is hidden not far from there.

That which for many centuries had been gathered (I,27)

We may believe that once the oak tree identified, the long-awaited hero will never have been so close to assuming the crown and to realizing the eschatological hopes of the Templar knights.

The unified space

In De Laudibus Novae Militiae, Saint Bernard writes about the Templars : «There is no social discrimination amongst them: respect goes to the best of them, not the most titled» (IV, 7). They wanted to lived in humility and fraternal equality, sharing citizenship without consideration for the titles of nobility which flattered the pride of the princes of royal blood. The Sons of the Valley are the followers of this Benedictine Strict Observance spirit of humility and equality.

The General Chapter was at the center of the functioning of the Benedctine Strict Observance, and its democratic principles determined the Templar knights organization in Jerusalem. Seven centuries later, this experience could be revived with a modern institution such as the United Nations established in Jerusalem.

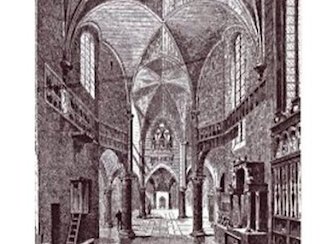

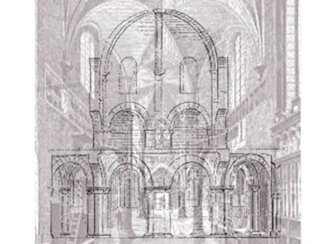

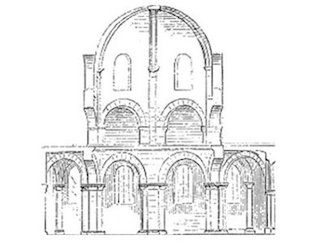

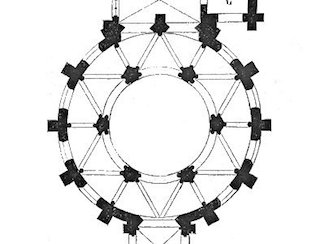

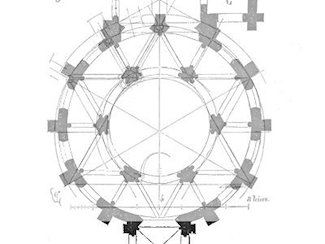

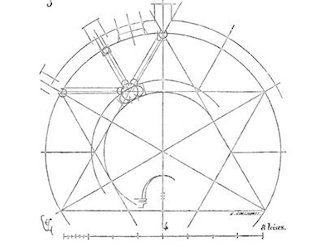

In the tradition of the Benedictine Strict Observance, the vision of the unified space is given to us by Our Lady The Virgin Mary, who offers consolation to the humble people in the valley. The unified space is a geometric method of plan drawing developed by the Cistercians for the construction of their churches dedicated to Our Lady. But it was also much more. The schema of the unified space was like the vision of the Holy Grail, it structured their relationship to the world in a new way – and incidentally enabled building construction. The understanding of this highly symbolic geometric knowledge was the key enabling the crusader knight on his journey to a New Life to reach the status of “citizen of the sky” , in the monks words .

The Florentine poet Dante Aligheri (1265-1321), who took Saint Bernard as a guide in the Paradise of his Divine Comedy, hid the principles of the unified space in his Inferno. Lucifer the “carrier of light” was set by Dante at the central point of this space. After crossing the perilous lands of Hell, the pilgrim reached the mountain of the Purgatory. For the Templar brothers – and this is very noticeable in Wolfram Eschenbach's Parzifal – little mattered whether the pilgrim was a Christian, Jew or Muslim. What really mattered was that he share the same vision of a unified space, so that their differences in religion wouldn't alter their ability to live together. At the top of the Purgatory, the pilgrim receives 'the crown and the mitre' to honour his free will lost with the fall of Adam and finally recovered. The journey from Inferno to Paradise has given him the insight into the unified space and, now a new man, he has earned the right to speak up in the Chapter where are gathered, sitting in a circle, these consoled brothers, the democratic citizens.

by Jean-Pierre SCHMIT